Vermicomposting Toilets

Vermicomposting (composting using earthworms) is a practice that many of us are familiar with, and is a great way of reducing the environmental impact of our household waste. Compost heaps are a great habitat for wildlife and a natural way of dealing with garden waste, whereas more controlled and closed systems can convert our kitchen waste into a natural fertiliser. The benefits of dealing with our garden and household waste are wide-ranging and include cutting the carbon footprint of our waste. However, kitchen scraps and hedge clippings are not the only waste that humans produce that can be dealt with by earthworms…

Types of toilet system

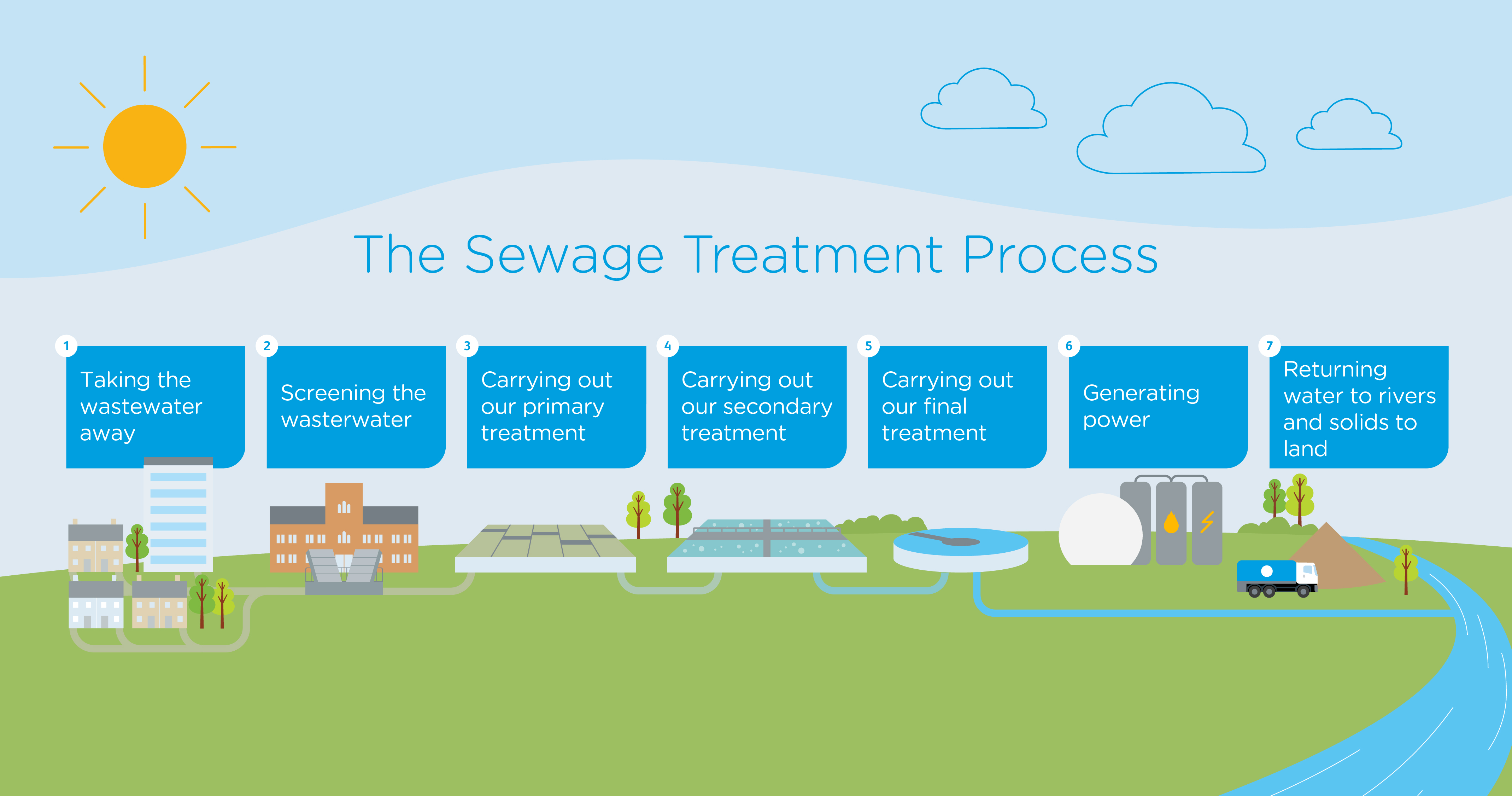

In the UK, human waste is generally flushed away into a centrally-processed sewage system. The waste flows through a sewer system to a sewage treatment plant where it is processed under anaerobic (without oxygen) conditions.

This system has revolutionised sanitation, but it has its disadvantages. Firstly, a lot of energy goes into treating wastewater in this way – increasing the carbon footprint of each toilet trip we make. Secondly, anaerobic treatment of organic solids has its problems – it’s slow, smelly and promotes pathogen growth.

An alternative to the flush toilet is the composting toilet. The term “composting toilet” usually refers to a dry toilet system, which facilitates decomposition of human waste by bacteria and fungi under aerobic conditions (i.e. an oxygenated environment). These are a great way of dealing with human waste locally with a usable output – compost. However, the process can be fairly slow and the compost may contain pathogens or residues of pharmaceutical products.

And that’s where earthworms come into the toilet equation. Different species of earthworm have evolved to thrive in different ecological niches, and in the UK we have 4 main ecological groups, which includes the compost earthworm group. The compost earthworms (such as Eisenia fetida and Dendrobaena veneta) inhabit environments that are rich in organic waste matter, such as decaying wood, animal dung and our compost bins.

Vermicomposting toilets are compost toilet systems that use earthworms to process human faeces, urine and toilet paper. The system includes a conventional flush toilet and, like composting toilets, deal with the waste on site.

How do vermicomposting toilets work?

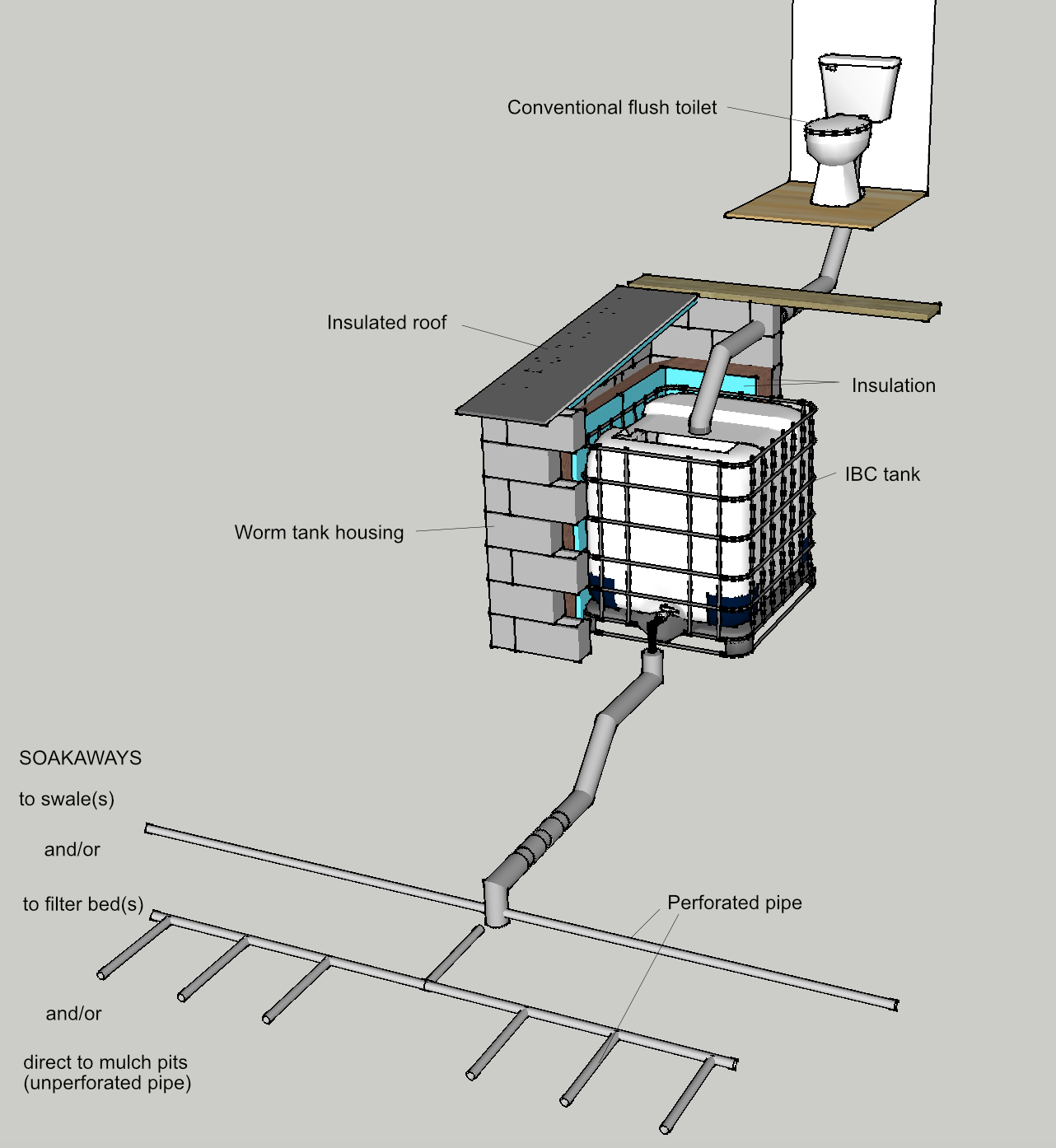

There are three main parts to the system:

- Conventional flush toilet – no need to change your toilet to install the system!

- Worm tank

- Soakaway (or ‘Greenfilter’)

Worm tank

The worm tank is where the wastewater meets the worms. It is recommended that Intermediate Bulk Containers are used as these are designed for storing/transporting liquids and have a central access hole on top and drain outlet at the base. An access hatch will need to be cut into the top to facilitate maintenance. The tank is then encased in insulated housing with an insulated roof to prevent the worm tank getting too hot in summer (cold winters may slow down activity but are less likely to kill the worms than a hot summer).

It is important that the worm tank can drain to maintain a healthy compost worm ecosystem. Therefore, the internal pipework and a gravel layer are needed to ensure that blockages don’t form. To get your vermicomposting system going, the tank will need to be ¾ filled with coarse organic material and a small layer of kitchen scraps/partially finished compost/manure. Once the worms have been added and become established (this can take a month), the system will be ready to use. The recommended species is Eisenia fetida (the Brandling or Tiger Worm) and these can be sourced from compost bins or dung heaps where they naturally occur or sourced from online suppliers. The number of worms needed will depend on how many people will be using the system (see the Vermicomposting Toilets website for more details).

Soakaway

The soakaway is also known as a ‘greenfilter’. Piping takes the vermi-filtered water out of the worm tank into a filter bed that continues to clean the wastewater. The filter beds are filled with the same organic material used in the worm tank during construction. The greenfilter is sized according to the soil infiltration rates of the site and can also be in the form of mulch pits and swales in addition to a green filter bed. Indicator plant species are planted within the filter to facilitate monitoring of the vermicomposting toilet system health (this is explained in more detail in the 'System maintenance' section below). Colonisation occurs when the earthworm cocoons (egg sacs) from the tank wash out into the greenfilter beds within the system wastewater.

System maintenance

Maintaining a vermicomposting toilet system should be relatively simple. Use of household cleaning chemicals in your toilet should be fine and residues of such chemicals should not be detected in the filter beds. However, vermicomposting toilet owners may choose to use cleaning products that have better environmental credentials if they are concerned about potential impacts of chemicals on their worm tank populations.

Worm tank maintenance should only need to be occasional in a healthy system. The waste entering the tank is nitrogen-rich, which means it needs to be balanced with carbon-rich food for the worms in order for them to be able to keep on top of processing it. To maintain the correct carbon to nitrogen ratio (C:N), the system will need to be topped up with an organic material mix occasionally. If the level of organic material gets too low the C:N can fall and affect the health of the ecosystem – so maintaining the level at half full is advised. The first sign of an issue is likely to be odour. If this occurs you should check that drainage is still working and that a blockage hasn’t occurred. It’s also worth noting that the tank should not need emptying, but you can periodically remove some of the vermicompost and worms to use on your garden if you wish.

Your greenfilter will need to be monitored as the indicator plants tell you how healthy the system is. It is recommended that you include some plants that require high nitrogen levels to thrive (such as citrus trees and roses). If the vermicomposting toilet system is healthy, these plants should begin to show signs of nitrogen deficiency after a few years (for example yellowing of leaves). By spreading manure at the base of these plants, you should notice their health improve relatively quickly.

Acknowledgement and further information

Keiron Brown is the Recording Officer for the ESB. His role includes delivering training courses, verifying records and supporting recorders to keep the National Earthworm Recording Scheme running.

This article was produced by Keiron Derek Brown using the Vermicomposting Toilets website content under the Creative Commons Licence detailed below. The Earthworm Society of Britain would like to thank Wendy Howard for allowing use of these materials. For further details regarding how to construct a vermicomposting toilet please see the website below.

www.vermicompostingtoilets.net

This article was produced by Keiron Derek Brown using the Vermicomposting Toilets website content and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Join us now!

Join us now!